His body was returned to Algeria and buried in a cemetery of the Algerian revolutionary army. He read the page proofs in September and died in December 1961, at age 36 in a hospital bed in the United States. During his last year he battled the fatal disease while writing, in a fury of anger and passion, The Wretched of the Earth.

Fanon survived a couple of assassination attempts, but fell ill with leukemia in 1961. He was expelled from Algeria in 1957 by the French government for his participation in an Algerian nationalist strike, and served briefly as the FLN’s ambassador to Ghana. Finding his sympathies turning toward the Algerian Nationalist movement, Fanon joined the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), which sought to end French colonial rule. Fanon first went to Algeria as a member of the French colonial administration and, in 1953, became one of the directors of a French psychiatric hospital there. He later studied psychiatry in Lyon, France.

During World War II, when Martinique was occupied by the Nazis, Fanon fought for the Free French in Europe (the exile forces led by General Charles de Gaulle after France fell to the Nazis in 1940).

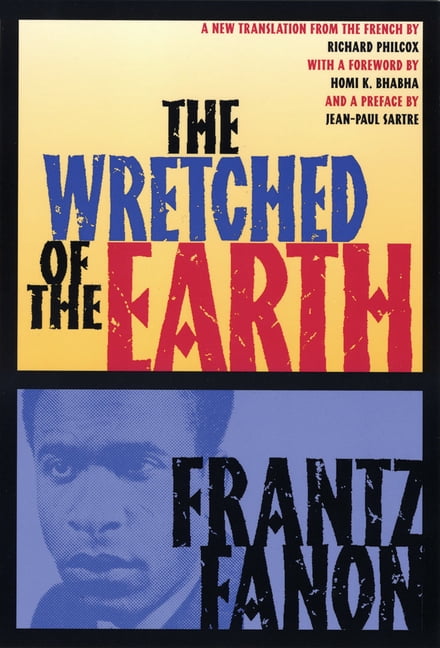

He was one of the 4 percent of black Martinique children whose families could afford to send them to lycée for a European-style secondary education. His argument leads into crucial notions about the issues of nation-building and national culture.Įvents in History at the Time of the Essaysīorn in 1925, Frantz Fanon grew up in a middle-class black family in the French West Indian colony of Martinique. A collection of essays, parts of which are set in Algeria and other developing nations of Africa, Asia, and Latin America published in French (as Les damnés de la terre) in 1961, in English in 1963.ĭrawing on his experiences as a revolutionary in the Algerian war of national liberation (1954-62), psychiatrist Frantz Fanon argues that only violent revolution can free the Third World from colonial rulers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)